It’s 11 December, a Sunday morning, and national elections are taking place in Romania. A middle-aged man is strutting through the dusted streets of a rural village in Giurgiu. He is saluting every person he meets on the streets, on their way to the polls, knowing them all by name; some handshakes here, some promises there, polite questions about kids and family. He is a veteran of Social Democrat (PSD) campaigns, going back to the early 1990s. On this occasion, in the 2016 elections, the PSD will receive its highest support in Giurgiu county, with almost 70% of the votes. It owes much of its success to people like him.

Meanwhile, a young woman is sitting in a downtown cafe in Bucharest. She is wired up with headsets and fingers glued to her smartphone, immersed in Facebook, as most of her friends will be voting; some likes here, some shares there, sarcastic comments about public figures and enthusiastic posting about newcomers to politics. She is a first time supporter and campaign staffer of the newly established party, the Save Romania Union (USR). The USR received its highest share of support in Bucharest, reaching almost 30% of votes. It owes much of its success to people like her.

But the campaign has been very different for the National Liberal Party (PNL), the main rival to the PSD. Their campaign efforts have been concentrated mainly in TV studios, with no noticeable territorial presence. When the results are tallied nationally, the PSD will have emerged with 45.5% of votes, the PNL less than half with just over 20% and the USR on 8.8%. Given that the PNL was the result of a merger, comprising two of the most important parties of the last decade in Romania (the PDL and PNL), that it is the party of the incumbent President Klaus Iohannis, and that it was supporting the popular outgoing technocratic Prime Minister Dacian Ciolo?, this score is drastically below expectations.

Generational divides and social cleavages

While these were the main stories of the election, the other parties that managed to get into parliament, although small in terms of their share of seats, will now play a key role in forming the governing coalition. These are the ethnic minority party UDMR (6.3%), former Prime Minister C?lin Popescu-Tariceanu’s party ALDE (6%), and former President Traian Basescu’s party, the PMP (5.6%).

In many party systems across Europe, party leadership has become detached from the lower ranks of the party, with voters left feeling unrepresented, and a space emerging for new competitors. In Romania, however, clientelistic linkages have allowed national parties such as the PSD to maintain a stable relationship with supporters, leaving nationalist newcomers (chiefly the United Romania Party – PRU) out of Parliament. Had the PSD diminished its territorial presence and linkages with supporters, we would have most certainly seen extremist parties become more prominent, as has been the case in countries like Poland and Hungary.

The big factor in the 2016 election was the absentee voter. Recognising that there was a stable PSD electorate in absolute numbers, the hope of parties on the right was to increase participation. And, indeed, there was some new enthusiasm displayed by the electorate, though it was largely apparent among young voters. Facebook was littered with messages of solidarity, enthusiasm and revolt. Even the coffee shops and university halls mirrored some of this excitement.

Following an increase in political activism and social protests, young voters have become involved in politics in bigger numbers than ever before. Just as young people in the early 1990s had developed a deep level of attachment to the political contenders of their time, the youth of modern Romania is now playing an active role, leaving a clear generational divide in Romanian politics. Older people were loyal to the Social Democrats, while younger but less numerous voters predominantly supported the PNL or USR.

This is not specific to the Romanian context, but rather an overarching trend. Generational divides were also a major factor in both the Brexit referendum and Donald Trump’s election victory. Social cleavages are increasingly important, with separate worlds coexisting in the same country now the norm for European democracies. This will prove to be a major threat to the forces of representation and legitimacy of any elected government (even one that is chosen by a majority of voters).

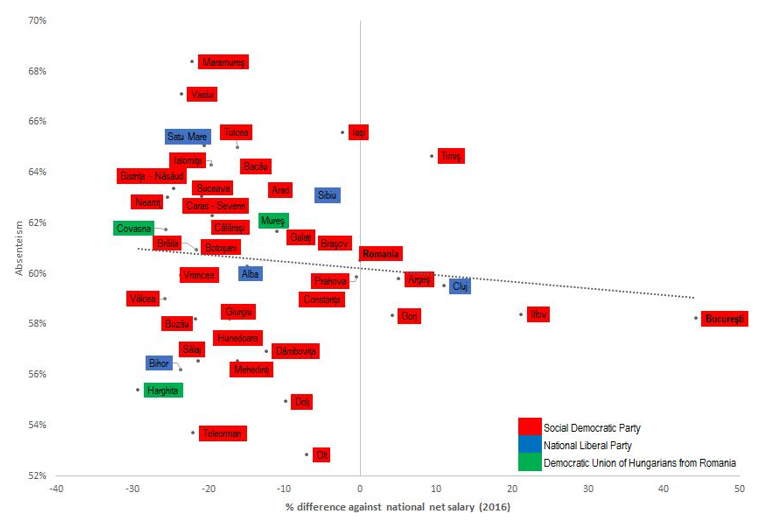

Nevertheless, if we look at the local level, there is little evidence of a clear cut profiling of supporters based on socio-economic status in the 2016 Romanian election. A subnational comparison across counties, which we have calculated below, shows that there is a strong and positive correlation between low income level or unemployment and lack of participation in the recent elections. In other words, the poorer, more disenfranchised localities were in fact the ones that had the highest rates of absentees. Despite public rhetoric, socio-economic profile was not the main trait of Social Democratic voters.

Figure 1: The link between turnout and average salaries in Romanian regions

Note: Compiled by the authors.

The real lesson in this case was that the voters who participated in the elections were those who had been mobilised. The highest turnouts were recorded in PSD strongholds like the Olt, Teleorman and Dolj counties. Similarly, the disciplined electorate of the Hungarian minority that is concentrated in the Harghita county also turned out in large numbers. These figures confirm the significance of territorial party networks.

Finally, beyond the social cleavages and demographic distribution, there is a generational divide in the political class as well. Political leaders have been used and disposed of at a much higher rate than before. Young leaders have stepped in for all the contending parties to replace previous generations tainted by corruption. They have, however, largely failed to meet expectations. They have often had insufficient time to gain institutional experience, which can be acquired, but they would need to survive in power for this to happen.

The clearest generational divide is with the newly established USR – seen by many as the political party representing the technocratic government now ending its term. In fact, many of the technocratic Ministers led the lists in the Parliamentary elections (for instance, Manuel Costescu, Cristian Ghinea, and Vlad Alexandrescu). These are young professionals, who have been educated and working abroad for several years, and have their roots either in the private sector or civil society.

Nevertheless, it is questionable whether the USR will maintain its current position. Other newly established parties have entered parliament before only to fade away in subsequent elections. They often find their support eroded by a poor territorial presence, or are unable to maintain their status as "outsiders" while in office. Indeed, new parties in Europe as a whole tend to have trouble surviving after a breakthrough. If the USR does survive, it will do so in spite of its current leader, and not because of him: while Nicusor Dan enjoys the admiration and trust of many of the party’s followers, he is more the leader of an inner circle than a charismatic politician who can appeal to wider society.

Future prospects

Currently, there is every reason to expect a new period of prolonged posturing between the President and the parliamentary majority. The tensions of cohabitation have become a recurring theme in Romania. As with the previous President, Traian B?sescu, incumbent President Klaus Iohannis has attempted to harness his prerogatives to the maximum. His open support for the technocratic government was a clear indicator of the President’s desire to exclude the PSD from office, but this no longer seems a feasible target. However, it might just help his chances of a second term in office if he provides a cautious form of resistance while developing a parallel agenda, with a stronger anchoring in foreign relations and regional security.

The results of the election also have implications in terms of the strength of the rule of law and anticorruption efforts. Backsliding in this area is probably unlikely, as long as Romania wants to remain close to the West. Furthermore, it is very likely that because of corruption charges, the PSD’s leader, Liviu Dragnea, will not be formally holding the PM office.

The nomination of Sevil Shhaideh as the first female (and Muslim) prime-minister of Romania while seeming radically progressive is in fact a traditional move given that she is a loyal and well trusted collaborator of Liviu Dragnea. Furthermore, she was the President of the County Councils’ National Union (UNCJR) – thus showing once more the significant role that local and regional organisations played in the Social Democrats’ victory.

It will prove difficult, if not impossible, to stop the formation of a stable Social Democratic government that will hold office during a period that includes symbolic landmarks such as the 100th anniversary of Romanian Unification in 2018, or Romania’s Presidency of the Council of EU in 2019. Between 2000 and 2004, under the majority mandate of the Social Democrats, Romania secured its membership in the European Union and NATO. If the governing parties prove to be responsible towards the future, they will work towards such goals as OECD membership, geopolitical stability and good relations with neighboring countries.

Ultimately, local networks, fueled by clientelistic practices, provided the resilience needed for the Romanian Social Democrats to once more achieve electoral success. But the emerging political representation and mobilisation capacity of young, particularly urban, Romanians is also noteworthy. These trends not only have implications for Romania, but serve as confirmation of wider regional dynamics. And when all is said and done, politics still requires an active territorial presence.